Researchers have devised a method to manipulate electronic friction—a persistent force within materials even at perfectly smooth surfaces—potentially paving the way for more efficient and durable technologies. While traditional friction is addressed with lubricants and surface engineering, this newly controllable force stems from interactions between electrons within the materials themselves.

The Problem with ‘Invisible’ Friction

Friction is a fundamental force opposing motion, essential for everyday actions like walking or striking a match. In machines, it’s a major source of energy loss and wear. Conventional approaches focus on minimizing mechanical friction, but even with perfect surface smoothness, electronic friction remains. This occurs because electrons within materials interact as they move, dissipating energy regardless of lubrication. The challenge is that this “hidden” friction continues to exist even when mechanical friction is negligible.

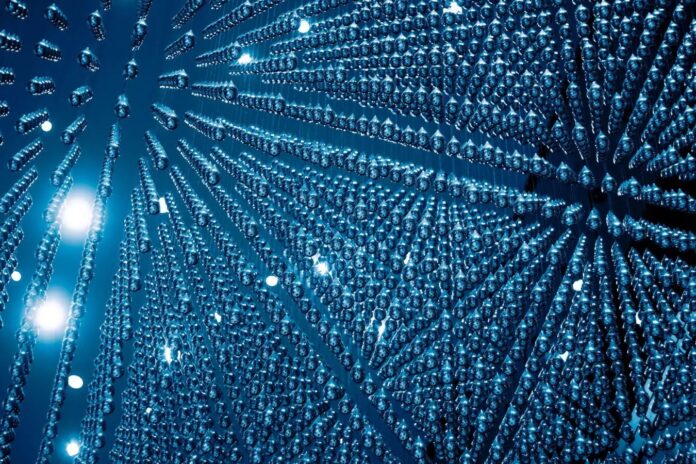

New Device Allows Electronic Friction Control

A team led by Zhiping Xu at Tsinghua University in China constructed a device using graphite and a semiconductor (either molybdenum/sulphur or boron/nitrogen). These materials are inherently good solid lubricants, meaning mechanical friction between them is almost non-existent. This setup allowed the researchers to isolate and study electronic friction. They discovered that even in perfect mechanical sliding, the movement stirs up electrons, creating energy loss.

Two Methods for Controlling the Force

The team demonstrated two ways to manipulate this electronic friction:

- Applying pressure: This forces electrons between the layers to share states, reducing energetically costly interactions.

- Applying a “bias voltage”: This regulates how much the electron sea is disturbed, effectively controlling the friction level.

They further refined the control by changing the voltage across different parts of the device, enabling fine-tuned adjustments rather than just an on/off switch.

Why This Matters

The first observation of electronic friction dates back to 1998 when researchers noticed its disappearance in superconductors at extremely low temperatures. Since then, the field has sought ways to control it without material replacements or additional lubricants. The ultimate goal, according to Jacqueline Krim at North Carolina State University, is real-time, remote control of friction—like adjusting shoe grip on demand.

Future Implications

While a comprehensive mathematical model linking all friction types is still under development, Xu believes these findings are promising for applications where electronic friction dominates energy waste or wear. This research could ultimately lead to devices with significantly extended lifespans and reduced energy consumption by addressing a previously uncontrollable source of inefficiency.

The ability to manipulate electronic friction represents a substantial step toward more efficient technologies, potentially impacting industries from manufacturing to consumer electronics.