Astronomers have identified two supernovas whose light, split by gravitational lensing, will reappear over the next 60 years, offering a unique opportunity to measure the universe’s expansion rate with unprecedented precision. This natural experiment could help resolve a long-standing conflict in cosmology: the “Hubble tension,” where different methods yield contradictory values for how quickly the universe is expanding.

The Cosmic Time Delay

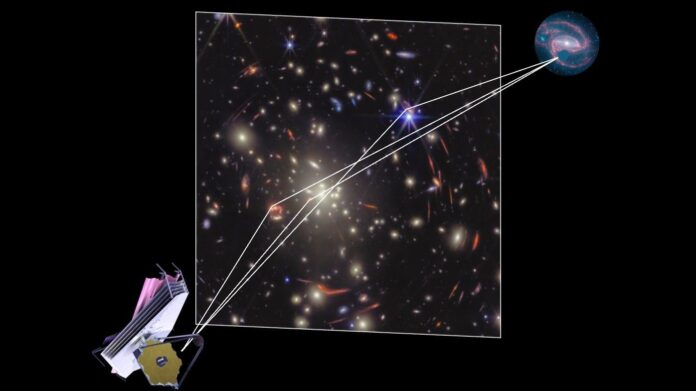

The phenomenon behind this breakthrough is gravitational lensing. Massive galaxy clusters act as cosmic magnifying glasses, bending and splitting the light from distant supernovas into multiple images. Each image travels a different path through space-time, leading to varying arrival times. One supernova, dubbed SN Ares, exploded almost 10 billion years ago; its light has already reached Earth. However, two additional images of Ares will arrive in approximately 60 years due to extreme gravitational time dilation.

The other supernova, SN Athena, is expected to reappear in the next one to two years. While less precise than Ares, Athena will serve as a validation test for our cosmological models.

Why This Matters: The Hubble Tension

The universe appears to be expanding at different rates depending on how scientists measure it. Observations of the cosmic microwave background (the afterglow of the Big Bang) suggest an expansion rate of 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec. However, measurements using Cepheid variable stars (standard candles) give a faster rate of 73 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

This discrepancy, known as the Hubble tension, is a major problem in modern cosmology. It could indicate that our understanding of the universe is incomplete, or that there are unknown systematic errors in our measurements.

The VENUS Program and JWST’s Role

The discovery of SN Ares and SN Athena is a result of the Vast Exploration for Nascent, Unexplored Sources (VENUS) program, utilizing the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). VENUS specifically targets dense galaxy clusters, maximizing the chances of finding these rare, gravitationally lensed events.

“Strong gravitational lensing transforms galaxy clusters into nature’s most powerful telescopes,” says Seiji Fujimoto, principal investigator of the VENUS program.

Before VENUS and JWST, fewer than ten such lensed supernovas had been discovered. Since July of last year, VENUS has already identified eight new lensed supernovas in just 43 observations, doubling the known sample size.

Looking Ahead: A Self-Consistent Measurement

The key advantage of this approach is that it provides a “single, self-consistent step” for measuring the universe’s expansion. By comparing the predicted arrival times of the lensed images with their actual observed times, scientists can refine their estimates of the Hubble constant independently of other methods. This is crucial in a field where systematic errors are hard to rule out.

The ultimate fate of the universe hangs in the balance. If dark energy weakens, the expansion could eventually reverse into contraction. Measuring the universe’s expansion rate with greater accuracy will not only help resolve the Hubble tension but also shed light on the cosmos’ long-term evolution.