For nearly a century, a small, worn limestone slab found in the Netherlands has puzzled archaeologists. The stone, etched with a simple grid, was clearly a game board, but the rules remained a mystery. Now, thanks to artificial intelligence, researchers have reconstructed how this ancient Roman game was likely played.

The Mystery of Coriovallum

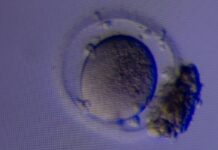

The board, just 20 centimeters across, was unearthed in Heerlen, a Dutch city built atop the ruins of the Roman settlement Coriovallum. The game’s origin and purpose were unknown, and no written records from the period detail similar pastimes. This lack of context is typical for many archaeological finds, especially those from everyday life; written history tends to focus on elites and events, not the leisure activities of ordinary people.

How AI Reconstructed the Rules

Researchers at Leiden University used an AI system called Ludii to simulate thousands of potential rule sets. The goal was to identify which rules would best explain the wear patterns on the stone, essentially letting virtual players “play” the game until a match was found. This is a groundbreaking approach, as it bypasses the limitations of historical records by testing possibilities directly against physical evidence.

The AI pitted two virtual players against each other, varying the number of pieces and allowed moves. The simulation determined that the game, now dubbed Ludus Coriovalli (“Coriovallum Game”), likely involved two players, with one controlling four pieces and the other two. The objective? To avoid being blocked first.

Blocking Games: An Unexpected Roman Pastime

The discovery is significant because blocking games, like Go or Dominoes, weren’t previously believed to have existed in Europe until the Middle Ages. Ludus Coriovalli doesn’t resemble modern blocking games, suggesting a unique Roman variation. This changes our understanding of ancient Roman entertainment, revealing a previously unknown element of their culture.

The Future of Archaeological Reconstruction

Archaeologist Véronique Dasen of the University of Fribourg calls the study “groundbreaking,” noting that the technique could unlock the secrets of other “lost” games. The research encourages archaeologists to re-examine Roman graffiti and other artifacts that might be game boards, but lacked clear identification.

The reconstructed game can now be played online against a computer opponent, offering a tangible connection to a piece of lost Roman history. The study demonstrates how AI can breathe new life into ancient mysteries, providing insights into past social life that would otherwise remain forever hidden.

The success of this method highlights a broader trend: AI is no longer just a tool for analyzing data but for actively reconstructing the past, filling gaps in knowledge where traditional methods fail.