In January 1816, Marie-Sophie Germain achieved a historic milestone: she was awarded France’s prestigious “Grand Mathematics Prize” by the Paris Academy of Sciences. However, the story behind this triumph reveals a deeper, unsettling truth about the systemic barriers women faced in science – even when their work surpassed all competitors. The Academy’s response wasn’t celebration; it was condescension and bureaucratic indifference.

A Prize Won in Isolation

Germain won for her groundbreaking research explaining how sound waves travel across flat surfaces. The Academy acknowledged her victory in a letter that barely concealed its disdain, noting she was the only entrant – a fact framed as a weakness rather than an achievement. They “grudgingly” offered to produce handwritten tickets to the ceremony “if needed,” implying her attendance was an afterthought.

Germain did not attend. Contemporary reports in Journal des Débats lamented her absence, framing it as a disappointment for audiences eager to witness “virtuoso of a new kind.” This phrasing underscores the novelty (and implied unsuitability) of a woman receiving such an honor.

Overcoming Obstacles: A Decade of Self-Driven Study

Germain’s path to scientific recognition was extraordinary. Born into a wealthy family during the French Revolution, she became fascinated with mathematics while secretly reading her father’s books. Her parents disapproved of her “unladylike” pursuits and actively tried to stop her, even taking away warm clothes to force her to abandon her studies.

Undeterred, she continued her research in secret, using candles and quilts to stay warm while studying number theory and calculus. When the École Polytechnique opened, barring women from attending, she bypassed the restriction by submitting answers to lectures under the pseudonym “Antoine August LeBlanc.” This allowed her to correspond with leading mathematicians like Carl Friedrich Gauss and Joseph-Louis Lagrange, who later became staunch supporters.

Solving the Unsolvable: The Chladni Figures

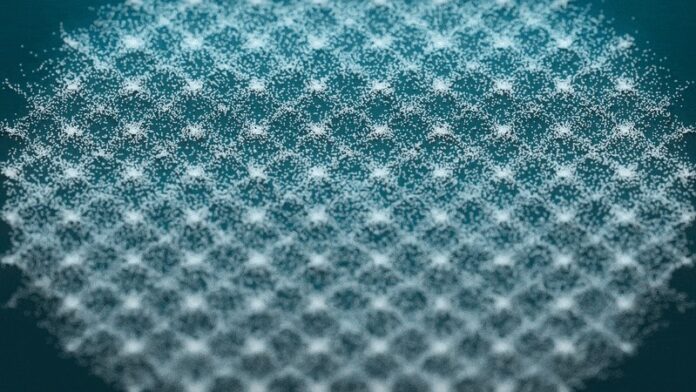

Around 1806, Germain tackled a seemingly impossible problem: explaining the geometric patterns formed when sand is sprinkled on a vibrating plate. The French Academy had offered a prize for a mathematical solution for three years running, but no one else attempted it, believing existing math inadequate.

Germain submitted solutions all three years, finally winning in 1816 with her paper “Research on the Vibrations of Elastic Plates.” While “awkward and clumsy” by modern standards, her work was a breakthrough in understanding 2D harmonic oscillation. The committee, however, barely acknowledged her achievement, with fellow mathematician Siméon Poisson refusing to discuss her work.

A Legacy Dismissed

Germain’s brilliance was often minimized or ignored. She contributed significantly to the proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem, identifying “Germain primes” (primes p and 2p+1) that laid the foundation for Andrew Wiles’s eventual solution in 1994. Yet, her theorem was relegated to a footnote in Legendre’s published work.

She continued her research for decades, but systemic prejudice persisted. Though Gauss pushed for an honorary degree from the University of Göttingen, Germain died of breast cancer weeks before it could be awarded. Her story is a stark reminder that even exceptional talent cannot always overcome deeply entrenched societal barriers.

The case of Sophie Germain illustrates how intellectual merit alone isn’t enough: historical context, gender bias, and institutional indifference all shape recognition and legacy.