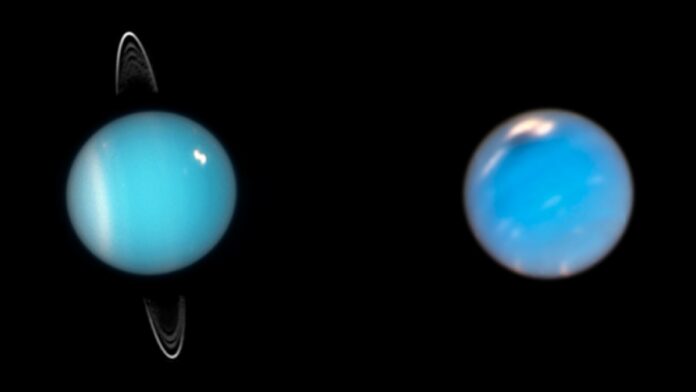

For decades, Uranus and Neptune have been categorized as “ice giants,” a label that may be fundamentally inaccurate. New research suggests these distant planets could contain more rock than ice, challenging long-held assumptions about their composition. This isn’t just about semantics; it affects how we understand planetary formation and the broader classification of exoplanets.

The Origin of a Misleading Label

The “ice giant” designation emerged to differentiate Uranus and Neptune from Jupiter and Saturn, the “gas giants” composed primarily of hydrogen and helium. Uranus and Neptune are smaller but denser, leading scientists to assume interiors dominated by water, methane, and ammonia ices. However, this classification has always been based on limited data. The only direct observations come from NASA’s Voyager 2, which visited both planets in the late 1980s.

New Models, Uncertain Composition

A team at the University of Zurich has developed a new modeling approach that doesn’t rely on strict compositional assumptions. By simulating numerous possible internal structures and testing them against observed gravity measurements, they found that both planets could be either water-rich or rock-rich.

“The name ‘ice giants’ also gives the impression that the planets are solid, but in fact, the materials in the deep interiors can be in liquid state,” explains astrophysicist Ravit Helled.

The models also suggest the presence of ionized water layers deep within both planets, which could explain their unusually tilted magnetic fields. The exact composition remains elusive, but the research suggests a far more complex internal structure than previously assumed.

Implications for Planetary Formation

If Uranus and Neptune are indeed rockier than believed, it raises questions about their origins. One theory suggests they formed closer to the Sun, where rocky material was more abundant, and later migrated outward. This idea aligns with existing dynamic models of planetary systems.

The Need for Dedicated Missions

Until we obtain new observational data, the “ice giant” label may be more misleading than informative. Determining the true composition will require dedicated missions equipped to measure gravity fields and atmospheric properties directly. For now, the classification should be treated as a placeholder.

The debate over Uranus and Neptune’s true nature underscores a critical lesson in planetary science: assumptions must be constantly re-evaluated in light of new evidence. Whether they retain the “ice giant” title is less important than understanding the complex realities of these distant worlds.